May 14, 2021 [left] vs. March 5, 2022 [right]

Time for an effort post.

It has been 8 months since I was diagnosed with type-2 diabetes with an A1C level of 9.4%. For those of you not familiar, A1C is a measure of average blood sugar levels over the past 3 months. A normal A1C is 5.7% or below, prediabetes is defined as A1C level between 5.7% to 6.4% and anything above 6.4% indicates full blown diabetes. The diagnosis happened 3 months after my 40th birthday and was simultaneously a surprise and not a surprise. Not a surprise because I had been classified as having blood glucose levels in the prediabetic range at my prior medical checkup three years prior (annual visits delayed due to birth of two kids and pandemic) and a surprise because my mental model of life didn’t include having a major metabolic disease at age 40.

The diagnosis probably should not have been as much of a surprise as it was, there were plenty of early warning signs. I would feel extremely tired in the afternoon and had started to notice my phone screen was blurry. At the time of diagnosis I weighed 281 pounds, had been diagnosed with sleep apnea 7 years prior and had just been told that I had a slight astigmatism in my eyes that would require a prescription for glasses.

The first few days after the type-2 diagnosis consisted of being in a very grumpy mood, mostly at the prospect of never being able to eat the foods I loved again. Once I got past the grumpy mood, there was a decision to be made: what do I do with this newfound information? Change nothing and continue down the path of metabolic disease or get my shit together and figure out what needed to be changed to prevent further damage?

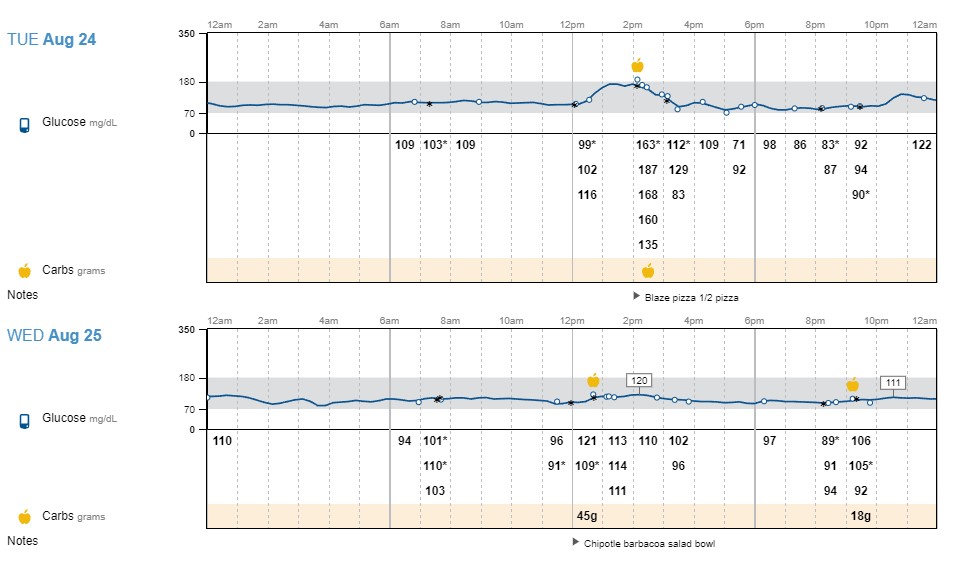

I recall one of my first Google searches after diagnosis being ‘what foods can a type-2 diabetic eat?’. That search landed me on a blog post by Alan Shanley which resonated with me immediately. Instead of providing a list of specific foods, Alan suggested something called “eating to your meter”. This approach meant using a glucose meter to take readings prior to eating, 1 hour after and 2 hours after and keeping a log to see what foods and and amounts of foods caused glucose spikes. Alan’s advice, plus other things I learned reading Alan’s book (What on Earth Can I Eat) and Jenny Ruhl’s two books (Blood Sugar 101 and Diet 101) showed me that it was possible to control my blood sugar levels by paying attention to what I ate. I also realized how little I understood about nutrition, given that I never thought twice about the impact that foods like pasta, rice or bread were having on my blood sugar levels. I previously, obviously incorrectly, assumed that blood glucose levels were a function of drinking soda and eating sweets. <insert sad-sounding game show buzzer sound here>. With this data in hand, one could adjust food intake to avoid these spikes. This data driven approach was much more appealing than spinning the wheel o’ random diet and hoping for a positive outcome.

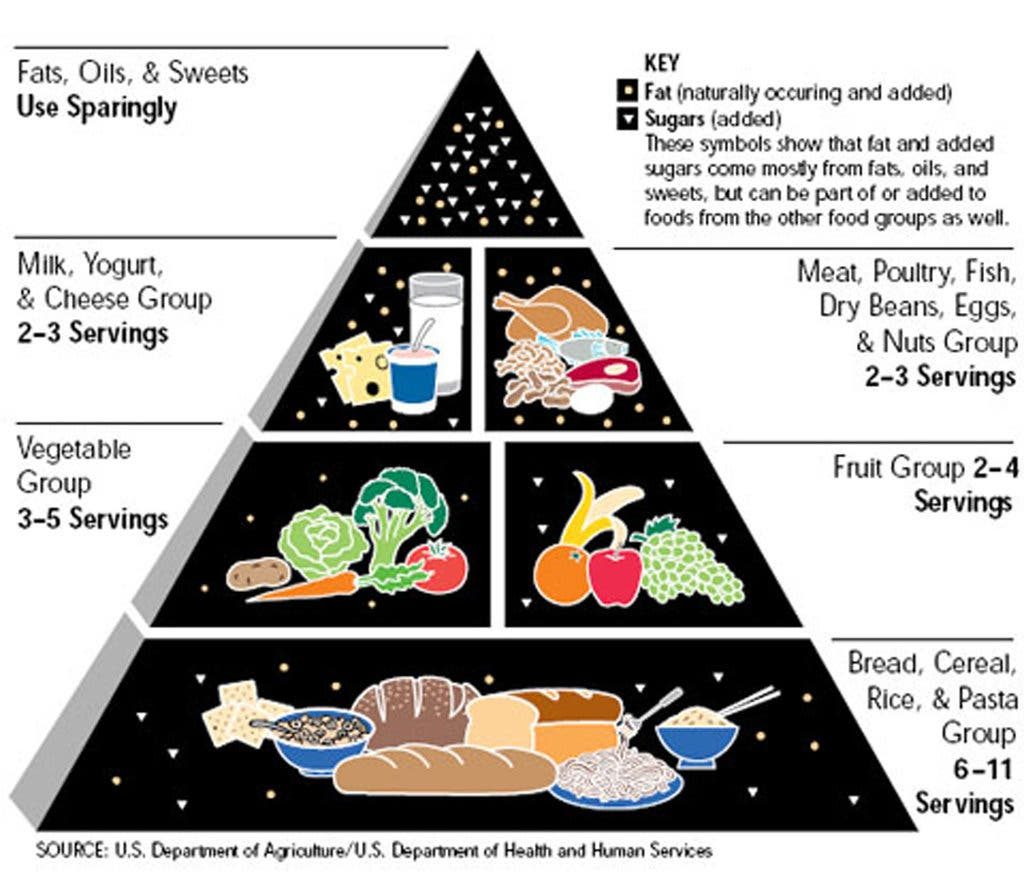

It did not take very long with this method to realize that excessive carbohydrate intake was the cause of my glucose woes. This excess-carbohydrate discovery also lined up with experiences shared by other type-2 diabetics online who suggested adopting a low carb high fat diet and shared their own success stories using this approach. This nutrition advice was a bit of a surprise, as I, a child of the 80’s, had been raised on the USDA’s food pyramid guidance which suggested eating lots of bread/cereal/pasta, some fruits/vegetables, a small amount of dairy/meat and limited fat intake. Fat was always a thing to be eaten in moderation, but now the pyramid was flipped. The data I was seeing from my glucose monitor was quite clear that this historical diet was not doing me any favors, so it was time for a crash course in nutrition.

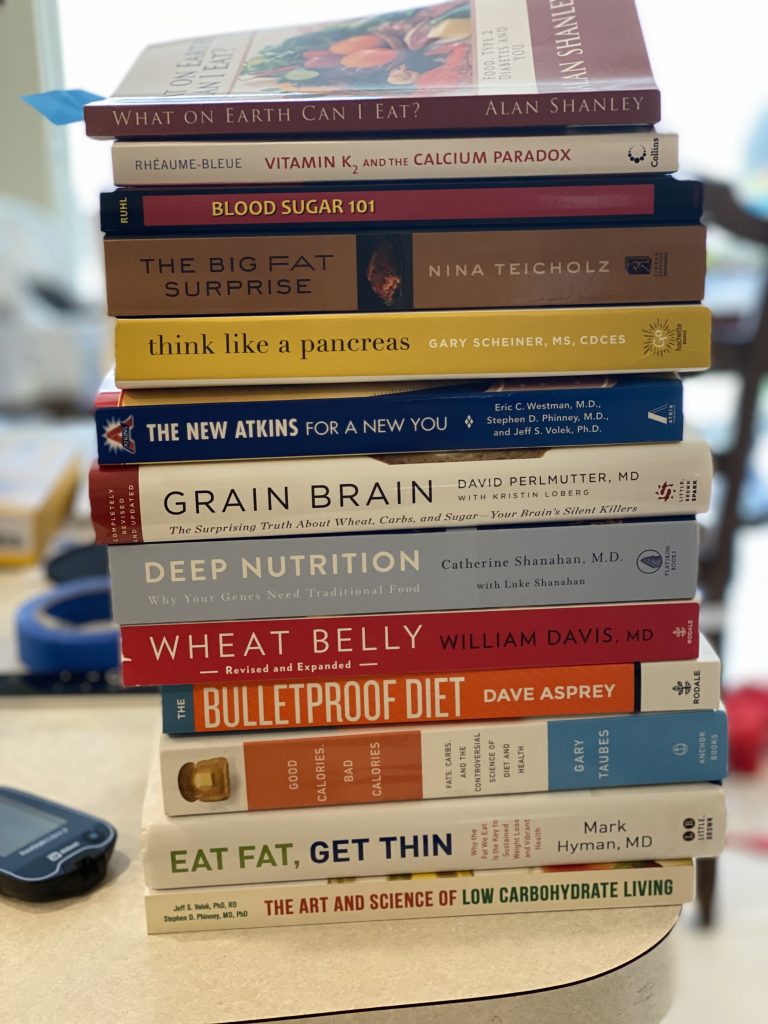

One of the next Google searches landed me on a YouTube video by a local cardiologist, Dr. Aggarwal. In this video titled ‘The Nutrition Detour’, Dr. Aggarwal outlined the issues with the Western diet. At the end of the video, Dr. Aggarwal provided a list of books for anyone who was interested in learning more about the material he had discussed. A few days later I had the start of a small library on health and nutrition courtesy of Amazon.

The books reinforced that the low carb high fat diet was worth pursuing and I was already seeing my weight drop without any changes other than adopting a low carb high fat diet. Seeing the weight loss without any additional exercise was fairly surprising and rather motivating. In addition to the weight loss, I saw immediate positive health changes in a number of other areas after a brief period of dietary changes, including but not limited to my vision quickly improving to the point of not needing to use my new glasses.

Somewhere around this time I got a prescription for a constant glucose monitor (CGM) which allowed for real-time monitoring of glucose levels without the need for manual finger stick tests. I stumbled upon posts by a reddit user /u/quantifieddiabetes/ who was also using a CGM to make data-driven decisions about food and participated in a community-driven experiment to measure the impact of vinegar on blood glucose after meals. Being able to see the visualized glucose data to provide the immediate impact of foods I was eating in real-time was a huge motivational benefit and a lot more convenient than performing a manual finger stick blood test 3 times per meal.

I had an opportunity to meet Dr. Aggarwal and he recommended adding books by Dr. Fung to my reading list. These books introduced the concept of intermittent fasting (IF) as a method to further improve glucose control and possibly put type-2 diabetes into remission, something all prior medical professionals told me was not possible. In addition to Dr. Fung’s books, two friends pointed me to the BBC’s documentary on intermittent fasting and to a New England Journal of Medicine review article on the topic. I realized that I had done some form of IF in the past when I would skip breakfast on a regular basis which is essentially a 16:8 or 18:6 fast depending on the timing.

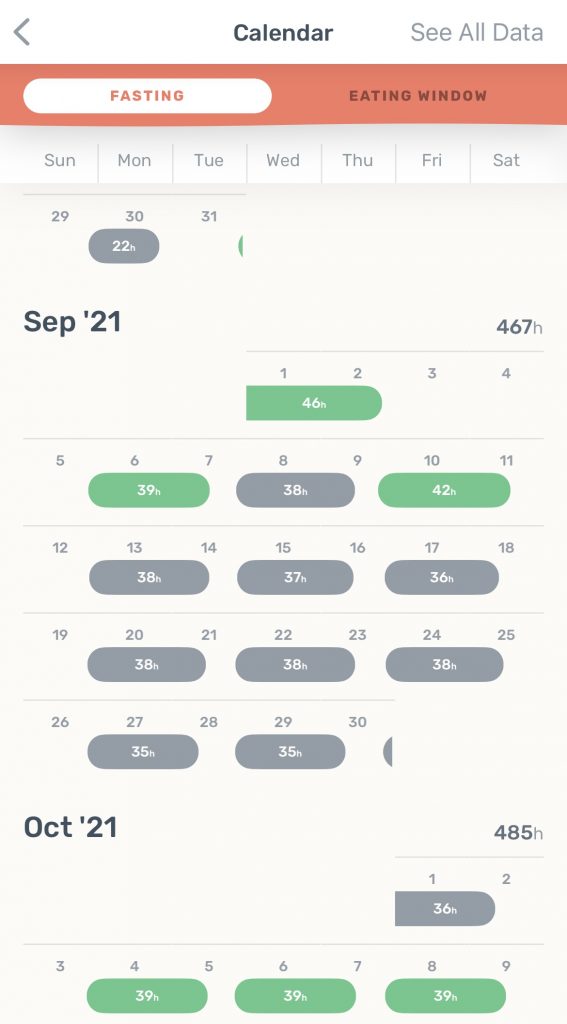

After watching the BBC documentary I decided to do a 24-hour fast as a philosophical experiment as it was quite clear there were gaps in my knowledge of nutrition/diet. What else did I not know about that could provide some nutrition/health benefit? The 24-hour fast went without a hitch, so I tried a 48-hour fast next which was also fairly uneventful. After the 48-hour fast, I decided to formally adopt some type of fasting schedule into my lifestyle changes to see what type of impact fasting would have. I decided to try a schedule that incorporated three 39-hour fasts per week. This meant not eating on Monday, Wednesday or Friday, eating only lunch and dinner on Tuesday/Thursday and having no fasting restrictions on the weekends.

Nearly 9 months after the initial diagnosis of type-2 diabetes, the impact of the low carb/high fat diet and intermittent fasting have resulted in the following changes:

- Type-2 diabetes put into remission within 2 months (A1C = 4.7 in September 2021 and remained at that level when tested again in December 2021).

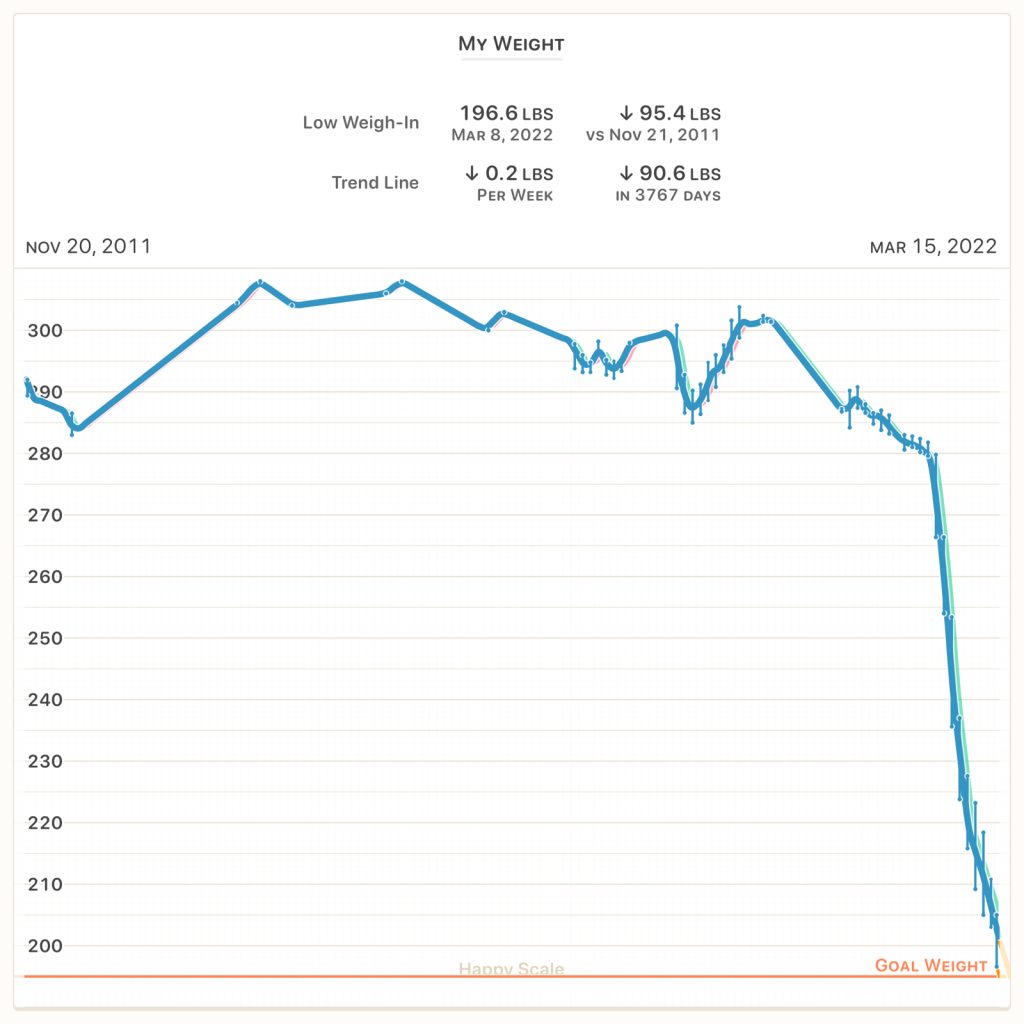

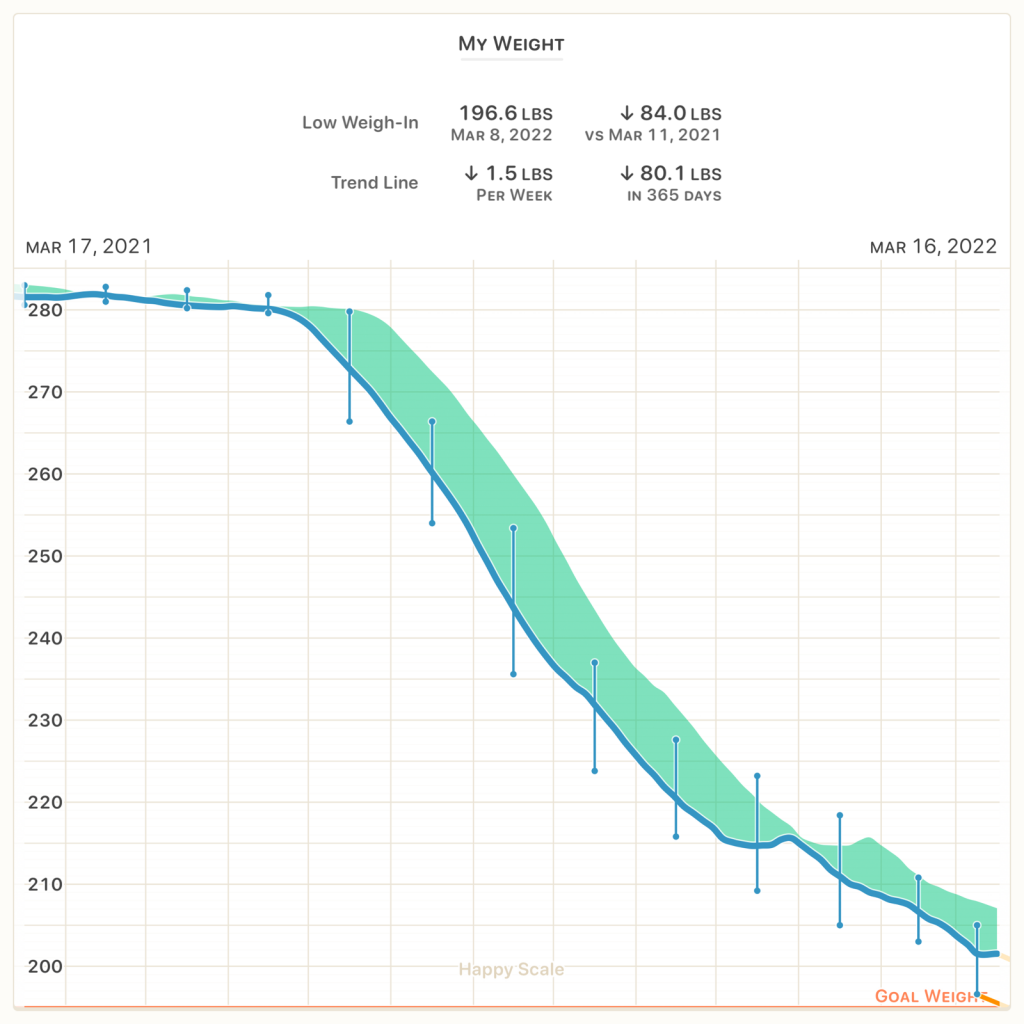

- Loss of approximately 80 pounds (starting weight 281 pounds on June 15, 2021; current 7-day moving average weight: 201.5 pounds). 44 of the 80 pounds lost was without doing any exercise whatsoever, only via dietary changes and intermittent fasting.

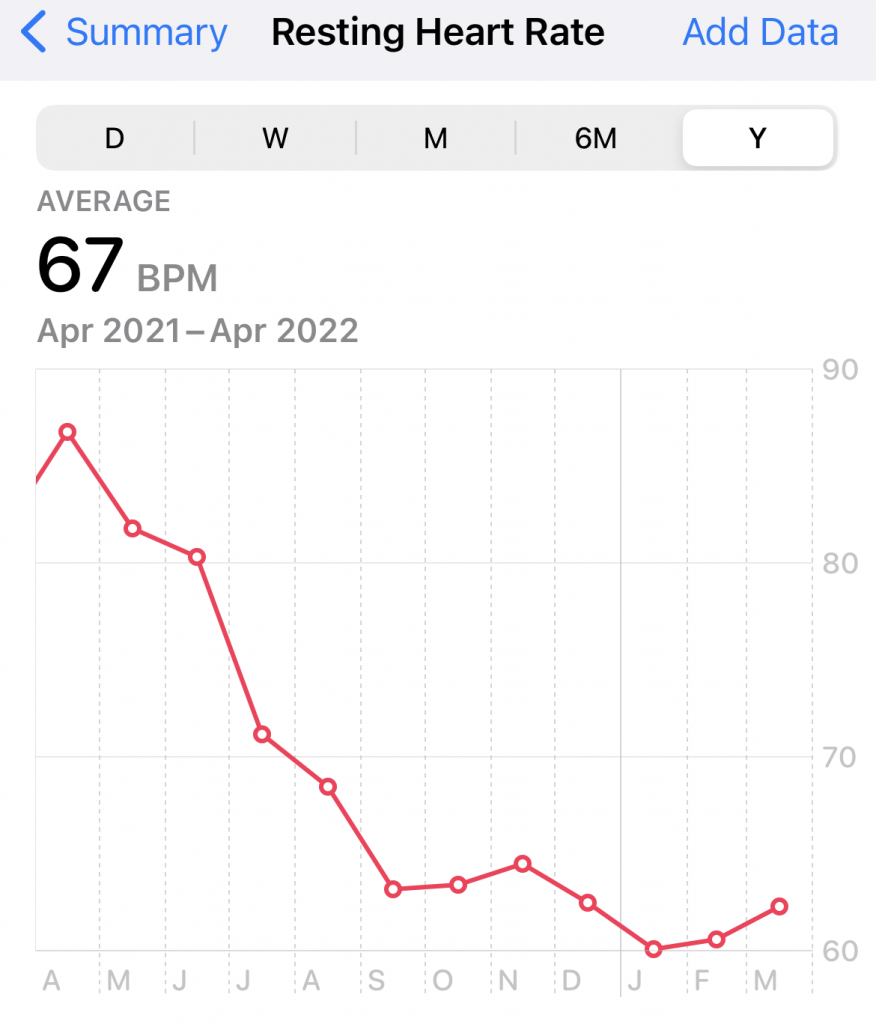

- Resting heart rate down from 87 bpm to the lows 60s.

- Triglyceride levels down from 319 mg/dL in June 2021 to 116 mg/dL in August 2021.

- HDL cholesterol (the good one) levels increasing from 31mg/dL to 35mg/dL.

- Sleep apnea appears to be in remission (results of sleep study pending, but no longer using CPAP machine).

- Discovered the ability to run. Started C25K program on October 4th, 2021 after I was ~44 pounds down. Completed C25K on December 11, 2021.

A few additional random thoughts/reflections:

- You cannot out-exercise a bad diet. Losing the initial 44 pounds without any exercise (At age 40! In the middle of a pandemic! With two kids under the age of 3!) on a low carb/high fat diet (Carbohydrate-Insulin Model) was far easier than any previous attempt at weight loss using a calories-in/calories-out (CICO) model (see 11 year weight history above).

- Humans are way more malleable than we give ourselves credit for, or at least than I ever thought I was.

- Gamification can be a great way to help new habits stick (I found the ‘Zero’ app to be great for fasting in particular).

- Using a moving average weight value to track weight loss progress over time was helpful to avoid day-to-day impact of weight fluctuation due to water/glycogen/etc. I love the ‘Happy Scale’ app for this (the two graphs above are from this app).

- If you are on a Keto diet or trying to monitor nutritional ketosis via fasting, get a blood-based ketone meter. It is much more sensitive for detecting low levels of ketones than the urine sticks. Being able to track ketone levels to fasting zones (anabolic/catabolic/fat burning/ketosis) can be quite motivating when you are first starting with fasting.

- There are a ton of great supportive communities related to these topics on Reddit including: /r/keto, /r/intermittentfasting, /r/omaddiet, /r/diabetes, /r/c25k.

- I am no longer using a CGM or performing manual finger stick tests after meals. I was able to collect enough data over the past few months to update my mental model of what I should be eating. I still do a manual finger stick test each morning when I get on the scale to monitor fasting glucose trends over time.

Obvious disclaimer: I am not a medical professional. Nothing on this page should be construed as medical advice. Just sharing my own lived experience in case it may be of utility to anyone else.